This is a fun post containing a lot of pictures and video clips. It will show you a wide variety of research topics within modern Computer Graphics. You might be surprised that some of these topics are done within graphics, but we can refer back to the definition in my first post to see how they fit into the bigger picture:

Computer Graphics is about modelling the physical world, using these models to capture the real world and to create physically meaningful things

Rendering

Let’s start by talking about the obvious research areas. 3D rendering has been a core area in graphics since the very beginning of the field. In terms of our definition, rendering is about modelling how light bounces off of objects and using this model to create images of scenes.

Rendering is considered a fairly mature subfield these days. Here are some of the specific topics that are still investigated in rendering

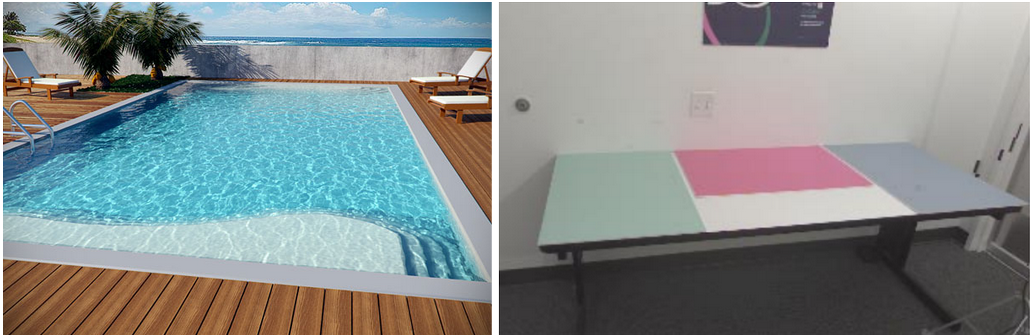

- Realistic lighting: Certain lighting effects, such as the patterns you see at the bottom of swimming pools or the bright red color of a table "bleeding" onto the adjacent wall, are traditionally hard to simulate in graphics. To make these kinds of realistic lighting effects, we have no better method than to simulate billions of individual rays of light as they bounce around the virtual world. Did you know that the entire IKEA catalogue is computer generated? They use this method to make their images. This is also how most movies render their computer-generated imagery. Research in realistic lighting tries to make this as efficient as possible, finding ways to simulate fewer light paths while still approaching the physically correct result, or finding ways to speed up the process of simulating light paths.

-

Real-time rendering: In contrast to movies, where the things you see are predetermined,

video games and virtual reality applications must be interactive - you can move your

character around, which changes where his shadows fall or where his flashlight is

shining. Figuring out how to render realistic lighting effects at interactive frame rates

is a big research topic, especially at companies such as NVidia.

From USC, the Digital Ira project aims to render a realistic human head, in realtime.

- Complicated materials: While things like walls and mirrors are easy to render, there are some materials that are much more complicated. For instance, skin and marble exhibit what is known as subsurface scattering, which is hard to model traditionally. See the Digital Ira video above for some really realistic skin rendering. Other materials such as cloth and sand are made up of small (but not microscopic) structures that play a large role in appearance even when you can't distinguish those structures.

-

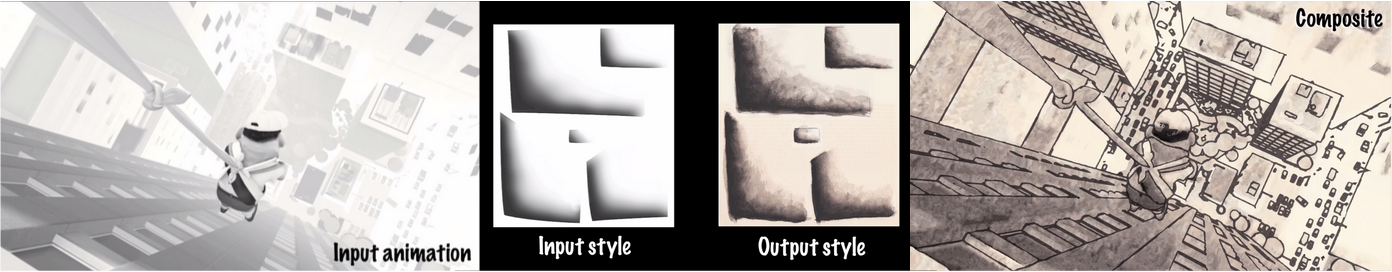

Nonphotorealistic Rendering: What if we want to render something so that it looks

cartoony, like a Disney movie? Nonphotorealistic rendering research looks at how

to do stylized rendering to achieve a certain effect.

Researchers at Pixar show how to automatically change the style of a 3D animation into a different one. Benard et al., Stylizing Animation by Example, SIGGRAPH 2013.

Researchers at Pixar show how to automatically change the style of a 3D animation into a different one. Benard et al., Stylizing Animation by Example, SIGGRAPH 2013.

Animation

Another unsurprising research area of graphics is animation. Animation is concerned with the dynamics of a scene, modelling how objects move and change shape over time. Here, the physically meaningful result is a video (or many still images) showing these changes.

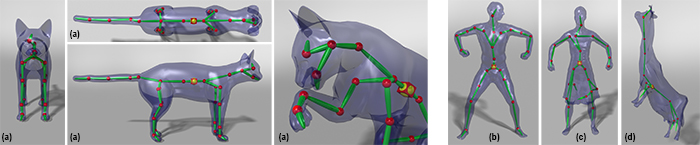

- Character animation has traditionally been done by specifying a set of “bones” (rigging), attaching the surface of a character model to these bones (skinning), and then specifying the angles of these bones relative to each other (animating). Most research goes into the last step, since it’s difficult to strike a balance between having a character’s movements look realistic and letting an animator control the movements of the character. At one extreme, animators specify the exact angles for every single joint in the character. At the other extreme, we have performance capture methods, where we track the movements of a real actor and then transfer those movements onto a character rig (but then if we want to change how the movement looks, we have to redo the capture).

- Instead of using bones and skinning, another way of animating objects just looks at how the surfaces of the objects move. This is often used to animate faces, but can also be used for more interesting shapes, as can be seen below.

- Facial animation is a very important area of research in graphics. We convey a lot of information in our facial actions and expressions, and being able to translate this into software is still not solved. Using many techniques from graphics and vision, researchers in facial animation have to model how our face shape changes, sometimes modelling skin on top of muscles and bone, other times only modelling the surface of the skin. Research in facial animation addresses both how to capture detailed facial expressions from an actor or user as well as how to use that information to control a virtual avatar or character model.

- A recent hot topic in animation is using machine learning or optimization to automatically figure out how to animate characters or creatures, without any manual control or motion capture. They’re lots of fun to watch!

Physical Simulation

Physical simulation is also about the dynamics of a scene, but while animation deals with characters and objects under animator control, physical simulation goes back to pure physics to model how physical phenomena naturally occur so that we can use this knowledge in our virtual environments.

- A favorite topic of physical simulation researchers is investigating how things collide, bounce, and shatter when they hit other things. The usual method for simulating these sorts of phenomena is using Finite Element Methods, which let us assume that everything is made of of very tiny discrete elements - imagine, for instance, approximating a circle as being made up of many small lines. The behavior of individual elements and their interaction with nearby elements can be formulated as mathematical equations, which can then be solved to get the results of the simulation.

- Hair and fur is hard to simulate: individual strands of hair interact with many other strands of hair, as well as with gravity, tension, and so on.

- Cloth is hard to simulate for similar reasons as hair and fur - many individual fibres in the cloth are all woven into each other.

- Fluid dynamics, how liquids and gases move and interact with objects, have been studied for a very long time. Highly refined finite element methods are the key to good fluid simulation.

-

You might be surprised to hear that sound simulation papers are published in computer graphics conferences as well! Sound is still a physical phenomenon, so it’s still covered by our definition (even though it’s not really “graphics” anymore). Sound is a vital part of making any virtual world seem real. Sound simulation papers can be divided into two categories: there are those that deal with how individual objects vibrate to create sound, and others that deal with how sound waves propagate through a scene.

Everyone knows what a plate falling onto a table sounds like. But can you predict what sound something will make just by looking at it?

An orchestra will sound different to a conductor than to someone sitting at the back of the concert hall; sound simulation can be used to help understand the effects of the shape of the environment on the sound that people hear at various locations in the environment.

Image and Video Processing

This category is more of a random collection of interesting things you can do when given images or videos. These are usually very application-driven. They often dealing with one longstanding problem with many works building off of each other, but there are also plenty of creative applications that nobody has thought of implementing before. Most of these works overlap significantly with computer vision.

- One common area of research investigates how to interpret images in a way that lets you edit the scene inside them. Similar effects can often be achieved by using lots of fancy photoshop techniques, but these are often mostly automatic. In terms of our definition, this type of problem requires a lot of modelling! We have to model how the image was originally formed, how the lighting in the photo works, and how objects in the scene relate to each other in 3D.

- There are many detailed motions in the world that are invisible to the naked eye, such as the vibrations of a resonating speaker or the regular reddening of someone’s cheek with their heartbeat. One group at MIT has devised a method to magnify these details using regular video camera or camera phone footage. These incredible results are not only physically meaningful, but are also things that we have never before been able to perceive visually.

- Big data in computer graphics is a fairly hot research topic. The premise is that, with the popularity of photo-sharing sites like Flickr and Facebook, there is an incredible amount of image data, on a scale that we’ve never considered before. There are many ways to use this data, here is just one novel example:

Fabrication

3D printing and fabrication have rapidly become a fairly popular subfield of computer graphics. The goal of these types of works is to be able to take a description of a 3D object, from things as simple as cubes to things as complicated as action figures, and make it physically into something you can touch and hold. Sometimes all we care about is making the 3D-printed model look like the virtual model, while other times we also want it to be able to bend or balance in certain ways as well! To do this we have to consider not only how the 3D printer works, but also how the material that the model is made out of behaves.

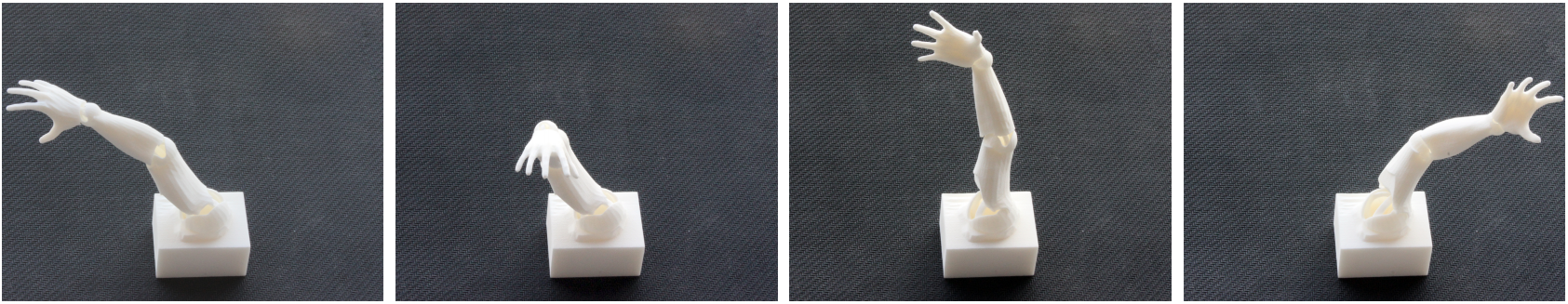

- While designing and printing simple 3D models is fairly well understood, using standard 3D printers to print models that are meant to move is still an active area of research.

- Another aspect of printing 3D models is making them have certain physical characteristics (while still maintaining their shape). For example, given a 3D model how do we print it so that it can balance standing upright? How can we print it so that it is as light as possible? How can we print it so that certain parts are flexible while other parts are stiff?

- Some of the most fun papers to read are those that use nonstandard methods and materials to make 3D models. There are papers about making 3D models out of beads, designing Rubik’s cube puzzles shaped like arbitrary models, sewing plastic sheets together so that they inflate into a certain shape, and so on. Takeo Igarashi, from the University of Tokyo, supervises a lot of this unique and interesting type of work.

Other

A grab bag of other topics covered in graphics

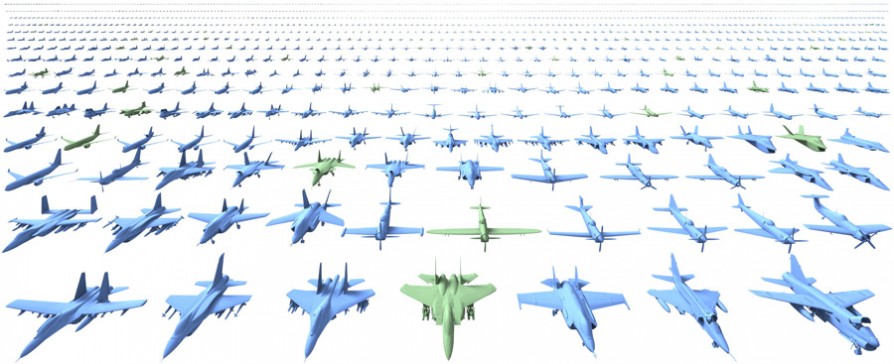

- Shape Analysis is a highly technical topic that deals with analyzing what components make up an object. For example, consider chairs: many chairs look radically different; some have backs or armrests, while others don’t. By understanding what makes a chair a chair or an airplane an airplane, it is possible to do such things as automatically generating new objects of the same type.

- New types of 3D displays are discussed at graphics conferences as well. Usually these papers come out of the MIT Media Lab or the University of British Columbia. In these types of works researchers must model how we see real 3D scenes and figure out how to imitate that using whatever devices they have available.

- New interfaces for interaction are one of the attractions of the SIGGRAPH conference; they are usually demoed at the Emerging Technologies venue but often also have associated papers presented at the conference. These works have a large overlap with Human-Computer Interaction; researchers have to model how people will use and interact with their technology as well as dealing with how to actually design and build the technology.

Conclusion

That was just a taste of the kinds of things that graphics researchers work on, and it is by no means exhaustive. I picked out some of the work with the most visually interesting results that anyone can appreciate, regardless of their technical experience. Of course, there are many other works that are much harder to show visually, such as some of the heavily mathematical topics or the ones that deal with hardware design. The SIGGRAPH Technical Papers Preview is always a good place to find impressive clips of graphics research:

- SIGGRAPH 2015: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XrYkEhs2FdA

- SIGGRAPH 2014: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3Z1hDwGEmM

- SIGGRAPH 2013: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAFhkdGtHck

- SIGGRAPH 2012: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cKrng7ztpog

The last post of my series is going to be more of a personal take. I’ll tell the story of my journey into graphics research, starting from how I got into graphics and ending with what I want to do in the future.