Paper at CVPR 2018.

Edward Zhang, Michael F. Cohen, Brian Curless. 2018. “Discovering Point Lights with Intensity Distance Fields”. The IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR)

Project webpage at http://grail.cs.washington.edu/projects/lightlocalization

TL;DR

Figure out where the lights are in a room, even if you can’t directly see them, from what the walls look like.

Abstract

We introduce the light localization problem. A scene is illuminated by a set of unobserved isotropic point lights. Given the geometry, materials, and illuminated appearance of the scene, the light localization problem is to completely recover the number, positions, and intensities of the lights. We first present a scene transform that identifies likely light positions. Based on this transform, we develop an iterative algorithm to locate remaining lights and determine all light intensities. We demonstrate the success of this method in a large set of 2D synthetic scenes, and show that it extends to 3D, in both synthetic scenes and real-world scenes.

Overview

This is a largely theoretical paper, which was a refreshing change from our previous paper. In that work, the only truly manual step was specifying the positions of point lights; in this paper we make steps toward automating that process.

The Light Localization Problem

Say we had a room lit with some number of point lights. if we know where the walls are, what color they are (independent of the lights), and what they look like when lit by the point lights, can we figure out how many lights there are, where they are, and how bright they are? This is the light localization problem.

Intensity Distance Field

The most important contribution in this work is the introduction of the Intensity Distance Field. This IDF is defined in the interior of the room, and answers the question “What is the brightest a light can be at this point?” We can compute this value by looking at the brightness of each point on the walls of the room (see the caption below). For more details, please refer to the paper.

How is this IDF useful? Here’s one intuitive way of thinking about it. First of all, we observe that most scenes have a relatively small number of light emitters in them. Since the total amount of light power in the room is constant, this means that with fewer lights each one must be brighter than if there were many. So we can use the IDF to prune away possible light positions: “Hmm, my IDF value is low here, so there probably isn’t a light here, since if there were, it wouldn’t be very bright.”

In the paper, we examine a slightly different intuition. Imagine I showed you the picture below and asked you where you thought the lights were:

You’d probably look at the two bright spots above the bookshelf and deduce that there were two corresponding lights on top of the bookshelf. This intuition is fairly simple: look for regions with a pattern that can be explained by one light (these bright spots). We use the IDF to construct a voting function where each point on the wall votes for where it thinks a light might be, and then guess that there is a light where many votes agree.

Note that, while the IDF is in some senses a fundamental construct of the scene, the voting measure is just one way of processing it to get information about the lights. I’m excited to see what other people come up with using the IDF!

Refinement Algorithm

The voting scheme above isn’t the end of the story. What if there are lights that don’t cast distinguishable bright spots? Maybe they’re really far away from walls, or maybe their bright spots overlap with those of other lights. This means that we might miss some lights, or we don’t get exactly the right positions (usually, though, we don’t have any false positives – that is, we won’t guess there is a light somewhere where there isn’t actually one nearby). We develop a simple refinement algorithm that lets us do a little better than just using our initial guesses.

We first use our voting scheme to guess at where some lights might be. We still don’t know if we’ve got all the lights, nor do we have the brightness of the lights we do know about. Let’s run a thought experiment:

Imagine that we had a magic wand that could do the following: If you pointed the wand at (or almost at) where a light was, it could give you a switch to control that light (no gaming the system by pointing at every spot in the room). With this power, we can just point the wand at each of our hypothesized light locations and turn off those lights. Then the room will only be lit by those lights we missed, so we can just recompute our voting function, make some more guesses, and repeat.

OK, that made things a bit too easy. What if instead, the wand gave you a dimmer switch to control the light you pointed it at, except the dimmer can just dim forever (making the light into a negative light) so you can’t simply turn the light off anymore. Now, what we’d do is point at each of our hypothesized lights, and then dim each of them just a little bit. If we recompute our voting function, it will be slightly different, but it will probably end up giving us the same guesses again. So then we dim each of them a little bit more, and then repeat. Eventually, we’ll have removed enough of the effects of our initial guesses that the bright spots for the remaining lights will be more distinguishable.

This dimmer wand idea is basically our algorithm: we essentially add “negative lights” where we believe the true lights to be, and gradually make the negative lights more powerful until more lights are revealed. There are some extra nonlinear optimization steps in there as well.

Results

Since this is mostly about the theoretical contributions, I won’t say too much about our results. We ran a bunch of experiments on synthetic data in 2D, a few synthetic examples in 3D (these end up taking a really long time in 3D), and also tried it out on two real-world datasets.

The 2D synthetic data was generated randomly in a diffuse convex room with no occlusions. While some reviewers complained that testing on scenes without occlusions or specularity limited the scope of our results, we wanted to specifically show that our method worked on scenes that existing methods were unable to handle at all. More simply, if we were to test on scenes with shadows and reflections, it would be too easy (and existing methods could do better than ours). Our algorithm was very successful, even when we added some noise to the data. It was not perfect, but most of the time when we got things wrong were when the solution had some inherent ambiguity – for example, a bunch of lights clustered together in the middle of a room could well be confused with a single light.

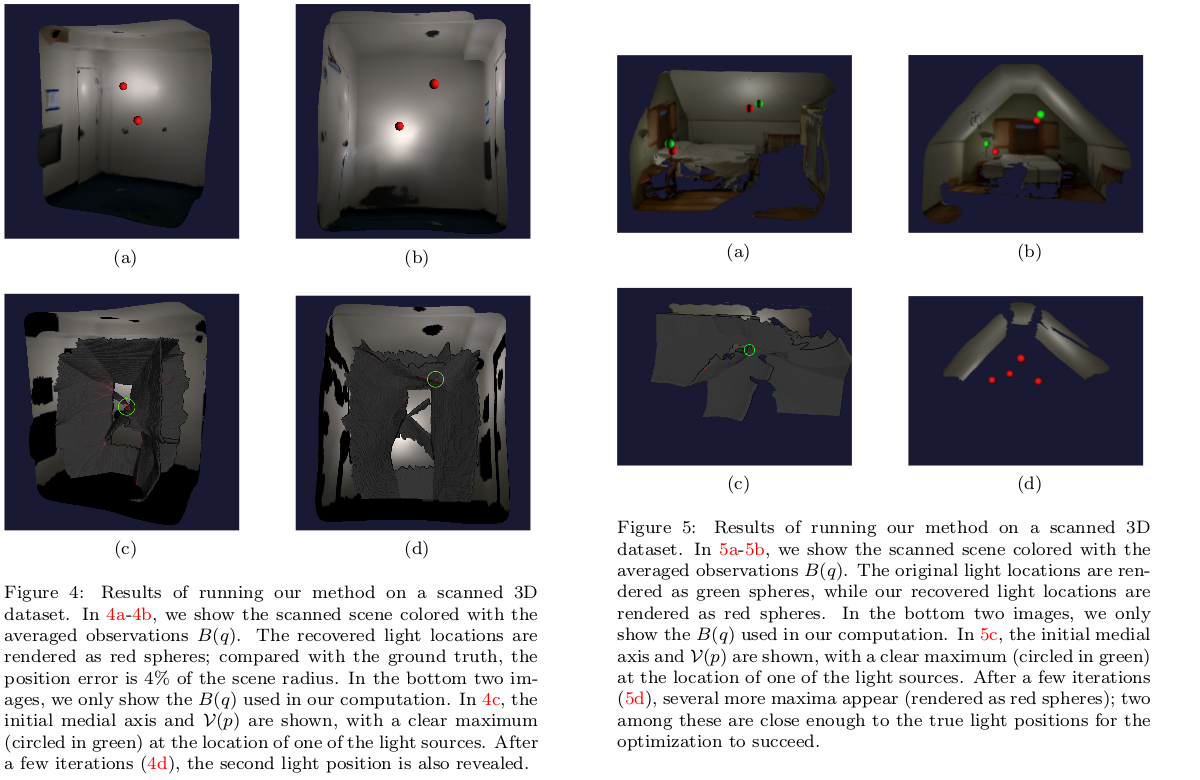

Here are some figures from our paper showing the 3D synthetic and real datasets:

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NSF/Intel Visual and Experiential Computing Award #1538618, with additional support from Google and the University of Washington Reality Lab.